Fishing

In 1972, aged 12, I was invited by my cousins for a week of outdoor adventure on their island, Eagle's Nest. It is a drop of an island in Trafalger Bay, which is part of the Northern Lights Lakes in Canada. I spent that week building a tree fort, swimming in the clear cool water, and fishing.

Only on my last day did I catch a fish, an event that startled me as I had given up hope. What surprised me most was how the fish fought. Though it wasn't a large lake trout, it took everything I had in my little arms to reel it in. I remember nothing beyond bringing the fish in, the thrill and satisfaction of that. Certainly the fish was killed, cleaned and eaten. But not by me.

This July I've returned to the island with my cousin Polly and I knew fishing would be a part of our time, in between the swimming (and birding). Since 1972, I've fished but one other time so I have not perfected my cast or my technique on bringing a fish in (that trip in 1972, I lost a lot of lures, irritating the adults who had purchased those lures). Before we left on this trip, Polly left a phone message: you have to club the fish dead. I left a message in return: no way.

The island holds a sort of mythological place in my life. That week in 1972 played a big part in my early love for the outdoors. There on the island I experienced a life lived close to the rhythms of the birch and hemlock, the trout and loons. It was a life I knew I wanted. I was curious how these early, perhaps glorified, memories would measure up to what is there. And I worried that perhaps age and the mess of life would intrude on the simple beauty of being there.

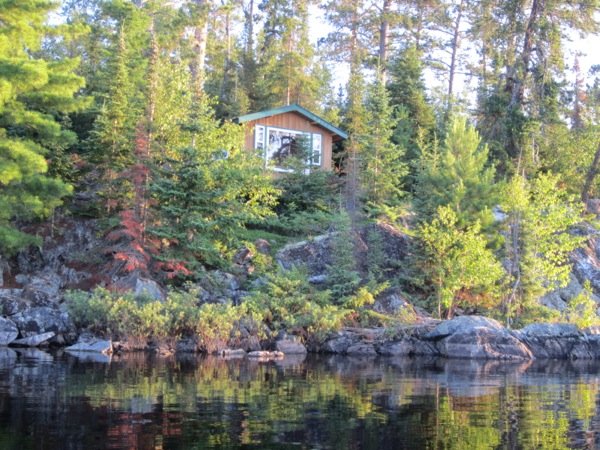

Except for a new large cabin built by my cousin Andrew, the island is remarkably the same as I remembered it. The light in the main cabin remains muted, perfect for games of backgammon or scrabble. Despite some (wonderful) improvements like a propane run refrigerator, the texture of life felt the same. There is no outside world, no internet or phone. The quiet is profound beyond all of my memories. In the late evening and through the night, the stillness was punctuated by the call of loons. Morning and evening the resident baby Merlins begged for food.

Our first full day, Polly woke me in my nest in the summer cabin, perched on a southeastern bluff, with coffee and fresh blueberry muffins. We then spent the morning swimming--naked--around the island. We pulled out on Blueberry Island and ate a few freshly ripe berries and warmed up. My hands were tingling from the cold. Our swim took hours, bobbing in the cold water, back stroke, breast stroke, a bit of a crawl. The day unfolded, endless and endlessly beautiful, except for the mosquitos. They buzzed our ears, bit our ankles and hands. These Canadian mosquitos made those I had encountered in Alaska in June seem fat, dumb and slow. These mosquitos had speed and agility on their side. I could smack one and it would rebound--flying off to bite again.

By late afternoon we were ready to venture out onto the water again, this time in a canoe. To fish. "You need to provide us with dinner, cousin," I said in mock seriousness. Polly had shopped for food for five for this week--we hardly needed any food. But I loved the idea of eating our own fish. I didn't bring up how it was going to get from the water to our plates.

We explored neighboring islands while Polly cast, and reeled in the line. The act alone felt right and good, the time meandering a pleasure.

So it surprised us both when Polly snagged the fish. It hardly struggled, but rather landed peacefully in the net I held. "Smallmouth bass," she said. It lay on the bottom of the tin canoe, without flopping or flipping. Later, we read about smallmouth bass: When hooked near the surface a smallmouth will ordinarily jump high into the air and can often shake the hook or lure from its mouth. When hooked in deep water the fish is a determined, powerful fighter, and even after it has been landed it flares its fins, clamps its jaw, and continues to look and act belligerent. The smallmouth bass is a fish that just won't quit." Really? So our fish's resigned calm became a mystery. But more: isn't fishing the most metaphorical of activities? In 1972 that fish had taught me about persistence, had given me insights into my little life, had maybe even contributed to the writer I have become. Forty years later, I wanted the same insight-inspiring sort of fight. Instead, this weak foot-long smallmouth bass had deprived me of some dazzling metaphorical insight about human nature, life and death. I was feeling mildly cheated as we made our way back to shore.

I quickly struck a deal: you kill the fish. I'll cook it. I saw that I had left Polly with the dirty work. She agreed, but she needed to be reminded of how to clean the fish. I fetched the Joy of Cooking, which contains information on killing and cleaning everything from snapping turtles to snipe and woodcock (I learn the entrails of woodcock are good flambed briefly in brandy).

Polly had no trouble scaling the fish. Then I read, as if from the Bible itself: "Next, draw the fish. Cut the entire length of the belly from the vent to the head and remove the entrails. They are all contained in a pouchlike integument which is easily freed from the flesh, so evisceration need not be a messy job." I contemplated the words integument and evisceration looking out on the water, while Polly executed her task. I read on, channeling Erma Rambauer, taking Polly through the steps of cleaning the fish. Polly's cleaning was a neat job. Erma would have been proud, and so was I.

Our fishing had not led me to thoughts on tenacity, strength, life and death. But as I stood there, looking at the lake, I saw that the real story is about cleaning the fish, facing the pouchlike integument. So much of life is about facing the pouchlike integument.

Our fish was tender and delicately flavored cooked in butter with lemon on the side. I thanked my cousin who had remembered to buy lemons, who had cleaned that fish without complaint. As we ate our simple meal, I felt that forty years had passed and yet no years had passed. We watched an orange sunset as calm settled over our isolated island.

Cousin Polly fishing; my cabin and writing retreat; sunset

RV in Alaska

I have always been fascinated with life on the road. My fantasy runs more to Travels with Charley than it does with those monstrous RVs that hog the road (what DO they have in there?) getting 2 miles to the gallon. To roam freely like a turtle with its shell had become a real fantasy. And my fantasy vehicle is the RoadTrek. It's sleek and runs on diesel and costs a fortune (just about what I paid for my house that doesn't roll around, and that will appreciate, not depreciate). It's a RoadTrek I had in mind when I decided we would rent an RV in Alaska. Instead, I found website after website of big fat RVs to rent. So that's what we would do.

The company I found online boasted they were homegrown Alaskan. Rave reviews followed. I booked early and got a discount. I was ridiculously excited about this leg of the trip, and imagined sending photos of me at the wheel of our rig, grinning as I backed into a camp site.

From the start it was clear that choosing homegrown wasn't such a good idea. When we were ready to go, at 9 on the morning, I called for a pick up. The message said, leave a message, but call back as well; I don't return phone calls. So I called a while later and they said the rig would be ready at noon. At noon they said 1:30. At 2:30 they said they'd pick us up in twenty minutes. At 3:45 they picked us up. At 4:30 we rolled out of the parking lot in a vehicle with nearly bald tires, that rattled (loose heat shield?), that barked (hole in muffler?) that had a cracked windshield and, we learned after being honked at a few times, the left blinker didn't work. I won't even begin to list the problems inside, like the passenger seat that flopped backward and would not lock, or the refrigerator that froze all of our food, or the shower that leaked. Sitting in the RV felt like being suspended in a hammock as we swayed from side to side rolling down the road. It was not a good feeling.

First stop: Walmart. In my strongest moments I find Walmart a challenge. I staggered out with our food for the next nine days. Second stop: the airport where we hoped PenAir would have delivered our luggage that did not make it onto our return flight from St. Paul. It was supposed to be in at 4:30. It was not, but they promised it would arrive at 7:30. It didn't arrive then either.

So luggage-less and in our swaying vehicle we made our way out of Anchorage. A gloom settled into the RV as we both took in our situation. Our plan to drive the Denali Highway vanished as we realized this RV wasn't reliable enough to drive the dirt road. What if we got a flat? the RV rental refused to give us a jack. "You'd never figure out how to use it."

I read the description for a camping spot outside of Palmer, a suburb to Anchorage. "Beautiful views of the Matanuska Valley," it said. A series of RV stacked in a row occupied a vast, characterless field. "Beautiful," I echoed as Peter pulled in.

I hardly slept through the night under our polyester sheets as I went through the ridiculousness of this venture. Driving a big, clunky vehicle is not an adventure; it was just midnight anxiety. We woke to walk down a mosquito-infested dirt road in search of Hammond's Flycatcher. No bird but the walk did, for a moment, distract us from our situation.

The drive out the Glenn Highway is one of the most beautiful in the world. In the distance, the snowy mountains of the Wrangell Mountains. The black spruce that line most of the road give a sense of true wilderness. A Northern Hawk Owl swooped across the road, a Robin in hot pursuit. There was little room to pull over but Peter got the RV off the road and we ran back to find the Owl perched on top of a tree. A mate joined it and the two sat there, staring at the world.

Excited by our owls, we rolled forward. We had expected to already be in Paxson by this night, but the RV wasn't much good over 50 miles per hour, so we were short of our goal.

The Tolsona Wilderness Campsite at one point had nesting Great Gray Owls--what could be more thrilling? So we turned in there for the night. We had a site right next to a stream, an open and beautiful place to sleep. Turning off the engine of the RV was the sweetest moment. Peter leapt from the driver's seat, relieved to be done with the narrow, often shoulder-less road in a fat vehicle. We needed a walk, so headed toward the gravel entrance road, intending to go in search of those owls (a search we knew would be fruitless, but we had to try). A squirrel caught his eye, and when Peter focused on the squirrel he saw two little brown blobs at the base of a large spruce tree. "Owls!" he said, practically walking up to them.

Two baby Boreal Owls huddled together, staring at us. Their wide eyes were framed with white, but the rest of them was a downy brown, the fluff of babyhood. There is nothing as magic as an owl. But a baby owl--I was shaking with the excitement of this. Others staying at the campground caught wind of our excitement and came over to look. A little boy peered into the woods. I handed him my binoculars. "Look closely," I said. "You will never see this again in your life." I was speaking to myself.

Through the night I woke a few times, wondering if those little owls were safe. A family of Ravens had set up camp on the other side of the river. The baby Ravens--nearly full size--made a racket asking for food. I didn't trust those Ravens not to take the owls.

At three in the morning Peter woke to the noise of the baby owls begging for food. He went out and recorded their cries. Later in the morning we visited them both, eyes closed in contentment, perched on tree limbs off the ground.

And here is how my logic works: if we had a light and fast car, or even a smooth riding RV, we never would have stopped at this campground, we never would have seen those baby Boreal Owls. I didn't start loving the RV--that would be going too far--but I saw that it was a part of this magical evening and night sharing a campsite with baby Boreal Owls.

Me, smiling at the wheel of the RV (a fake smile); two blobs of Boreal Owl; close up of Boreal Owls--photo by Peter Schoenberger

St. Paul

"Hey Mr. White Man, have a good life." The Filipino worker leaned over the staircase, cigarette in hand. He was calling out to the tall thin white man in front of me as we left the dining hall at the Trident Seafoods plant in St. Paul. St. Paul is a tiny island, one of two, along with St. George, which make up the Pribilof Islands in the Bering Sea. The Trident Seafood plant has the only food service on the island. So that is where we ate during the two days were were on the island.

The first time we walked in, the smell of fish smacked me upside the nostril. Interlaced with this was the tang of cigarette smoke. Once in the galley, the thickness of fried seafood took over. Our group of birders assembled meals from the salad bar and the range foods: rice, chicken, baked potatoes, and one night pasta, ravioli. The tomato soup was delicious; so was the carrot cake. We ate at long plastic tables, while a TV blared from one end of the room and a radio clattered from the kitchen. Everyone stared at the TV; no one spoke. The Trident workers, few of whom were white, ate in silence as well. They had just finished the crab season and a board in the hallway announced it was a good season: everyone would receive a $400 bonus.

"So Mr. White Man, where are you going from here?" I asked the young man. He had spent the past six months processing King Crab and was off to work in Wrangell processing salmon. "Today I got to see the seals for the first time," he said.

The seals are the Fur Seals. 1,000,000 Fur Seals migrate to the Pribilof Islands; in July, at the height of the breeding season, a seal pup is born every five seconds. While we were there, the males had arrived after months of swimming in the cold Bering Sea. We peered at them from blinds as they lolled on beaches or draped across the rocks. They were waiting for the "girls to show up," as one of our guides described it. Those females carry their babies for 11.8 months. So they arrive, give birth, then mate again before returning to the cold waters.

Our group spent our time at St. Paul watching all of the alcids that nest on the island, but also admiring those seals, which look like giant sausages on land. They would scratch with their flippers, and some would tangle with each other, but most just slept, the lazy sleep of an animal that has not been on land in months.

St. Paul is not an easy place to get to. We flew from Anchorage, stopping for fuel in Dillingham, and then flew on to St. George where some passengers deplaned. St. George is St. Paul's sister island, and is often shrouded in fog so few flights actually land. We got out of the plane under a cold blue sky and walked the airstrip. As we admired the views, cannons popped off in the background to set off the birds, which otherwise take over the runway. There, I saw Grey-crowned Rosy Finch, a large rose hued finch with a clean grey cap, and Red-legged Kittiwakes for the first time. I spoke with a woman who lives on the Island. She surfs offshore and that afternoon was going to kayak to the point. It seemed like a small paradise.

On the final leg of the journey I learned that the woman next to me was on her way to St. Paul to make it her home. Her young son and daughter sat in the seats behind us. Her husband was doing weather work on the island and had been living there since April. "I had some movies to see," she said with a laugh as a way to explain why she was only now arriving at her new home. "I'm not an island person."

St. Paul would be an interesting place to call home. There is a cluster of tidy houses, a Russian Orthodox Church and one store that sold 12 ounce bottles of water for $2.99 and four frozen cobs of corn for $13. There is some tourism on the island because though it is also frequently fogged in, it is more accessible. The island Native corporation (TDX) has also hired three young men, all fantastic birders, as guides to take visitors around. They greeted us at the airport, and walked us to our rooms at the King Eider Hotel. To call this a hotel is a bit of a stretch. The "hotel" is a hallway that runs parallel to the waiting room of the airport. Spare, clean rooms awaited us, with a bathroom down the hall. Through the night, the northern sun streamed through the thin curtains.

Right away we headed into the field to walk a marshy patch near town. An Arctic Fox worked the edges of the marsh, delighting all of us. The fox are so numerous, prowling the cliffs for birds or their eggs, that by the end of the trip we were less excited by them.

The land is low, dried grasses with a few wild flowers coming into bloom--buttercup and a fuzzy lousewort. I could see that by mid-summer the island would be a riot of color. And a riot of baby birds. The island is where a range of Alcids nest and they were all clamoring at the cliffs that ring the island. On the next day we walked the top of those cliffs, peering over at the ocean, then snow that still skirted the cliffs, a reminder of the winters in this exposed place. Birds speckled both the snowfields and the cliffs, often just feet away from us. Least and Parakeet Auklets, Horned and Tufted Puffins, all clung to the cliffs. Common Murres with their white bellies and black backs (which make them look like Northern Penguins) sit in a bunch while the Thick-billed Murres line up in a row, often with their backs to the water. In between these alcids both Black-legged and Red-legged Kittiwakes zoomed by, often carrying nesting material. All of the birds were enchanting, but the Tufted Puffin is a favorite, with those fantastic tufts, a movie star of a bird.

A few low hills rise up on the island, providing great views in all directions to lakes and to the Bering Sea. From these hills we also hoped to be able to scan the wide sky for a White-tailed Eagle that had been seen a few times on the island. We never saw the eagle, but during those eagle watches I was able to listen to the lively song of the Lapland Longspur, admire more Gray-crowned Rosy-finch and a few Snow Buntings.

During spring and fall, migrants are often blown off course, and they end up here on the island, hunkering down in the crab pots, or in some of the ditches around the island. One evening we drove the bumpy dirt road to the northern end of the island. We fanned out, walking to the top of a hill, when our guide emerged with a big grin. "Wilson's Warbler," he said a little out of breath. It's a bird all of us know well from our homes in the lower 48. But to see it there amidst birds that were exotic to us was an odd treat. We chased down hill, then I spied the bright bird, put my binoculars to my eyes to see its dark black cap, and vibrant yellow body. A piece of home in a place that felt like a stark and beautiful and hard place to call home. I wished that mother and her two kids luck in the new St. Paul lives; I wished all of those fur seals good breeding; I hoped the tall white man has a good salmon season.

photos: the cliffs of St. Paul; Wooley Lousewort; Murres on the cliffs; count all of the Fur Seals!; the elegant Tufted Puffin, photo by Peter Schoenberger

Breeding Plumage

If I hear the words "breeding plumage" one more time I'll scream. When you travel for 18 days with focused birders, in June, in Alaska, a lot of what they are excited about (ok, what we are excited about) is seeing birds we are familiar with, but not in their breeding plumage. With some birds the transformation is extraordinary--they become different birds--and with others the change is minimal. One of my favorite birds, the Rusty Blackbird, has little variation between breeding and not. But the subtle shift from brownish bird to one that glows a range of blues and purple blacks is marvelous. And the Rusty Blackbird has a wonderful whitish iris, and makes a sound like a squeaky door. That this is one of my favorite birds is odd but my fondness for the bird is perhaps because it is overlooked in favor of those birds who do have showy breeding plumage. But also, it is a species in decline and I feel protective of animals that are not as colorful or charismatic that are threatened.The first time I saw a Rusty Blackbird Peter said to me, "This is a bird that might be extinct in our lifetime." That's a sobering thought. When our guide here in Alaska pulled a Rusty Blackbird out of the tundra near Nome, I was thrilled, while some participants sat in the van and waited for the next more exciting find.

All of the birds are here in Alaska to breed. In Nome, Anchorage, and on St. Paul Island, we have seen courtship displays, mating, nest building activity--lots of birds carrying tundra grasses to make nests--nests themselves, and some nests with eggs. It's a special thing to see these nests, built on the ground or in willow bushes as there are no trees in Nome or in the Pribilofs. There have been Hoary Redpoll nests, Red-Necked Grebe nests that appeared to be floating on the water, American Golden Plover nests on the hard Tundra at Wooley Lagoon. At a pull out near Potter Marsh outside of Anchorage an Arctic Tern had settled in right by the road--a serious bad choice for nest location--and dive bombed us when we got out of the van. On St. Paul in the Pribiloffs, a Lapland Longspur bolted from its nest as we walked out toward a marsh, and a Rock Sandpiper left its nest as we drove by. In each case, we looked quickly, not wanting the mother to leave her eggs uncovered for long in the cold northern air.

And some birds have already hatched. Cackling Geese and Mallards lead the pack. But at Westchester Marsh in downtown Anchorage we saw baby Mew Gulls--little gray spotted puff balls--and at Potter Marsh baby Sandhill Cranes, rusty puff balls.

Across from Potter Marsh is a strip of water, before the train tracks that line Cook Inlet. Our guide led us across the busy Seward Highway to peer into this strip of water. Karen, who has been a great spotter for all of this trip called out, "Grebe," with her Texas accent. And there, sure enough, was a Horned Grebe paddling in the water. It had wheat-yellow tufts that framed black cheeks and deep red eyes. It looked like it was wearing a beautiful, slicked back helmet. Its rusty chest gave way to a grayish patterned back. This was nothing like the black and white bird I had seen in New York State. This was the Horned Grebe in full breeding plumage. For once, those two words did not make me want to scream.

photos above: Mallard and babies; Lapland Longspur eggs; Rock Sandpiper eggs; American Tree Sparrow Eggs; Horned Grebe in breeding plumage! photo by Peter Schoenberger