Hiking Alone

I had wandered my way eastward to this trailhead, stopping at one of my favorite farms to admire flocks of Snow Geese coming in for whatever leftover corn they can find on their route south. Since I didn't know when or if I was going to hike this trail, I haven't let anyone know I'm out here. I know this is not smart--you should always let someone know your hiking plan. But I'm feeling cut loose in many ways, so I'm out here, wanting my inner and outer worlds to align.

It's a strange feeling, this sense of being unaccounted for. It’s not that there is no one to care; it’s that no one is allowed to care. I want to feel alone. This could lead to a sense of loneliness or alternatively, to a slight euphoria, the elation of freedom. It's the later feeling that took hold as I started up the steep trail.

I had wandered my way eastward to this trailhead, stopping at one of my favorite farms to admire flocks of Snow Geese coming in for whatever leftover corn they can find on their route south. Since I didn't know when or if I was going to hike this trail, I had not let anyone know my plan. I know this is not smart--you should always let someone know your hiking plan. But I'm feeling cut loose in many ways, so I was out there, wanting to walk into that sense of alone.

It's a strange feeling, this sense of being unaccounted for. It’s not that there is no one to care; it’s that no one is allowed to care. This could lead to a sense of loneliness or alternatively, to a slight euphoria, the elation of freedom. It's the later feeling that took hold as I started up the steep trail.

I don't mind that the trail is steep, but I do mind that it's covered in leaves; it was hard to tell what might give and what would take my weight. I slipped a lot, reaching for tree limbs to stabilize me. As I climbed, I felt my heart thumping in my chest. I liked how solid it felt, pushing against my ribs.

Three men and two dogs appeared on the trail above me. They were sliding down the trail, hanging onto trees and rocks, sitting down to maneuver over the larger boulders. I pet the collie dog’s long, fine nose and asked her if she wanted to join me. The men laughed as we continued in our opposite directions. As I turn and briefly watch them slide down to the parking area, I thought: Now I am out here alone.

While we climbed in the canyon, we had some friends who--when they were not stoned--knew where we were. It was small but real comfort. But once we were in the park, we were on our own, in this day long before cell phones. Once a week I wrote to my parents to tell them where I was and what I was doing. I lied a lot in those letters. They thought I was sharing an apartment with friends; I was sleeping in a parking lot. I told them I was eating well; we had rice with powdered soup mix most nights. I wondered how long it would take before my parents reacted to the fact they hadn't gotten a letter. And then what would they do? Start searching the state of Colorado? What I realized is that we could disappear and it would be weeks before anyone would sound the alarm, come looking for us. It was a strange thought to have at age eighteen but it was a strong and unnerving one. Perhaps it arose because Munch and I were so lost that summer—in our lives and on the rocks--and had a lot of what we jokingly called epics. But it was also because I had a deep sense no one was paying attention. My father was immersed in writing a novel, my mother absorbed in her translation work. Then, I did want someone to care.

A wind picked up. It gusted over the top of the mountain chilling the sweat on my back. I stopped, drank some water, pulled on a hat. My binoculars dangled at my stomach, but I hardly had use for them. I pished at a squeak from the bushes and a Black Capped Chickadee obligingly appeared to keep me company. They win for most inquisitive, cheerful bird. Down in the valley I could see a long marshy area, which led to a pond, dotted with hundreds of something—ducks, geese—that were too far off to identify.

At the summit of South Brace rests an enormous rock cairn. On clear views there would be views into Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York. Instead, the wind kicked up, gusts that smelled like a storm, like bad weather. I kept on down the trail heading for the summit of Brace and after a hundred yards stopped. I pulled out the map and calculated how far I had to walk to the summit. It seemed ridiculous not to get there, but I didn’t want to get caught out in a storm, adding rain or snow to my slippery descent. I turned around and headed back down the trail.

In Rocky Mountain National Park, Munch and I headed for an area known as Lumpy Ridge. We didn’t have a guidebook, but rather a piece of paper with a few notes on it. “The Book,” “Pear Buttress,” “Sundance.” These were the names of the hunks of granite that soared several hundred feet into the thin air. “Do you think this is the Book?” we would ask each other. But on one day we did a climb named “J-crack,” an unmistakable crack, shaped like a J in the middle of a vast granite wall. No one knew where we were, but for one long day, we knew where we were. And that was a relief.

I was just nearing the descent of the steep section when my ankle buckled under me. I stumbled. The pain shot through my ankle. I sat on a boulder and rested. I drank some water, ate the peanuts I had brought with me. I wiggled my ankle to see if the pain remained.

When I was twelve, I sprained an ankle on the summit of Mount Nittany, which shadows my hometown of State College. College students partying at the summit came to my rescue. They fashioned a stretcher out of tree limbs and denim jackets—this was the early 70s when everyone wore a denim jacket. Four young men hoisted the improvised stretcher and carried me the mile and a half to the car. I felt foolish and they felt heroic.

I knew that no one was going to come along and carry me down this mountain. And I knew I didn’t need that. This was a simple twist, the pain perhaps more imagined than real. But as I sat there I went through what I would do if I had to spend the night in the mountains, how I would set up a bivouac, how I would ration my water. It was when I started to imagine how cold it would get—I could hear the water of the iced-over waterfall—that I stood up and weighted my foot.

My first steps made me wince, but as I continued on, my ankle warmed and the pain dulled. I moved slowly, slithering over rocks, grabbing tree roots to help me down. And this story ends like hundreds before it, with me arriving too soon back at my car, and driving home warm and safe, the pull of exercised muscles overriding the emotions of the day, leaving me happy.

Foraged Thanksgiving

"Thanksgiving dinner?" I asked.

They smiled.

I could feel the elation of the hunt, the story of how they got this bird early on Thanksgiving day. I wanted to ask who was going to pluck the bird, clean it and cook it. There were a lot of soft brown feathers to deal with. For a moment I was jealous of the bird. Pheasant tastes delicious. But I knew I wouldn't be capable of killing the bird. And this day was devoted to eating only food we had gathered ourselves.

"Thanksgiving dinner?" I asked.

They smiled.

I could feel the elation of the hunt, the story of how they got this bird early on Thanksgiving day. I wanted to ask who was going to pluck the bird, clean it and cook it. There were a lot of soft brown feathers to deal with. For a moment I was jealous. Pheasant tastes delicious. But I knew I wouldn't be capable of killing the bird. And this day was devoted to eating only food we had gathered ourselves.

Jody knows these lands well, having lived in Provincetown for almost thirty years. She can lead me to the cranberry bogs, but also to where I might see some Horned Larks and Snow Buntings in the open grassy areas. At one beach there were seals floating nearby, heads bobbing in the cold ocean. We hoped to see whales but did not. Throughout the vast dunes, Jody pointed out fox prints, raccoon, coyote.

This year, the cranberries were sparse. In the past, we had plunked down in a bog and filled our plastic shopping bags. But the first bog we tried was bare. The second patch, nestled around small pitch pines, had a few berries. We worked for them, squatting to see the few bright red berries, taking one or two, then moving on. After an hour we had perhaps two cups. Enough for our meal.

Pulling mussels was easy. We wandered, took a few, then wandered more at low tide. In the distance stood a huddle Black-Backed Gulls and a few fleeting Sandpipers. On the Bay side of the jetty, Common Eider floated near to the rocks, diving for fish. They have beautiful yellow bills and in the clear water we could see them paddling strong to gather their food.

People out for a walk before or after their turkey dinners asked us what we were doing. We boasted about our day of food gathering and a young woman from Manhattan looked incredulous. "Mussels grow here? and you just take and eat them?"

I am no prophet of right eating. I eat organic when I can, eat meat when I want to, but live by no rules. And yet I know we are divorced from what we eat. For one day, I want to know where my food comes from. And I want to know that I could provide that meal. But it's all a game--I wouldn't last long like this and the truth is, cranberries and mussels are not a great pairing.

Since those college days we have seen each other at least once a year. I make an annual pilgrimage to the Cape, where my parents spent their honeymoon and where their ashes are scattered in the dunes. I have known all of Jody's jobs, friends, loves—and her pets. On this trip there are two new orange cats George and Fred, and Griffin, the wonder dog who as a puppy joined us on a forage day. We both ponder aloud our single lives. There is no regret; we are both enjoying our freedom, and the fact we are meandering freely together through this beautiful day.

River Time

We included Merle, who at age 72 teaches Outward Bound courses, has a shock of curly gray-white hair and a calm steady demeanor; Kate on her pedal boat, after shoulder surgery, long legs shoving south; and me, on a short fall break from teaching, desperate not to think about faculty meetings. The most important team member, however, was Neena, a pint sized dog, which Kate had just rescued. This was Neena’s river baptism. To keep her happy--and who doesn't want to keep a dog happy--we stopped every hour to stretch and pee and marvel over how slowly we were moving.

We included Merle, who at age 72 teaches Outward Bound courses, has a shock of curly gray-white hair and a calm steady demeanor; Kate on her pedal boat, after shoulder surgery, long legs shoving south; and me, on a short fall break from teaching, desperate not to think about faculty meetings. The most important team member, however, was Neena, a pint sized dog, which Kate had just rescued. This was Neena’s river baptism. To keep her happy--and who doesn't want to keep a dog happy--we stopped every hour to stretch and pee and marvel over how slowly we were moving.

We needed a campsite in this unlovely place. Room for three tents, three boats, three tired women. Papscanee Island is not quite an island, and is rimmed with wooden pylons, visible at low tide, and beyond the pylons, rocks covered over with...asphalt. The asphalt was often cracked in a yawn to reveal a jumble of rock teeth. The Hudson River Watertrail guide states "There is no river access for boaters." But, we needed access into the trees. And that is what we found, directly across the narrow river from a set of oil tanks.

Once dark settled in, once we had eaten our magnificent burritos--all river food is delicious--we realized that the spot lights from the oil tanks were going to keep us company through the night. I had been yearning for the quiet that is sleeping with my back to the ground. But that is not what we had that night. At two in the morning a barge arrived, pushed by a roaring little tug. And they began to offload oil, using enormous diesel powered pumps. They were still pumping when we pulled our near sleepless bodies from our tents.

"That wins for the worst campsite of my life," I joked.

You would think at this point I would speak of grumpiness, of bad temper, or perhaps even the nuttiness of this adventure. Instead, I'm going to write of giddiness as we shoved south, of wonder as I counted the bald eagles that soared over us, or perched in a nearby tree, fishing for their next meal. By the end of the day I had counted twenty-two of the big birds, birds that but twenty years ago had all but vanished from the Hudson Valley. I allowed myself a drop of hope.

First the wind gusted from the south, making our passage a trial, then it shifted to the north, making it a joy. We scooted along, and by four in the afternoon, we pulled onto the sandy shore of Gays Point.

The smooth river pulled me early from my tent, to oatmeal and coffee. Before we slipped into our boats, we stood with our toes in the water and "clapped on" the river. Merle spoke of the beauty and necessity of this river, our time on it. It was but a drop of time, but at that moment I felt like we had been there for days, weeks, my body settled into its aches, my mind into the quiet thoughts that emerged from what I saw. Nothing more.

Then we pushed south, wondering where our adventure would end. As I approached Stockport Middle Grounds, the first flock of Brant coursed by over head. Six more flocks of the small dark geese flapped by, bringing news of the Arctic, and of colder weather, of winter.

I was now in familiar land, reaches I had paddled many times before: Middle Ground Flats, the quirky village of Athens, the Rip Van Winkle bridge. I knew the zig zag path of the channel in this section and how the eastern shore is shallow at low tide.

Merle, Kate and I stood with our toes in the water and "clapped off." Merle spoke with a clear wisdom, thanking the river for our time, the company, the adventures had and to come. I had tears in my eyes as we all clapped our goodbye to the river.

Fishing

In 1972, aged 12, I was invited by my cousins for a week of outdoor adventure on their island, Eagle's Nest. It is a drop of an island in Trafalger Bay, which is part of the Northern Lights Lakes in Canada. I spent that week building a tree fort, swimming in the clear cool water, and fishing.

Only on my last day did I catch a fish, an event that startled me as I had given up hope. What surprised me most was how the fish fought. Though it wasn't a large lake trout, it took everything I had in my little arms to reel it in. I remember nothing beyond bringing the fish in, the thrill and satisfaction of that. Certainly the fish was killed, cleaned and eaten. But not by me.

This July I've returned to the island with my cousin Polly and I knew fishing would be a part of our time, in between the swimming (and birding). Since 1972, I've fished but one other time so I have not perfected my cast or my technique on bringing a fish in (that trip in 1972, I lost a lot of lures, irritating the adults who had purchased those lures). Before we left on this trip, Polly left a phone message: you have to club the fish dead. I left a message in return: no way.

The island holds a sort of mythological place in my life. That week in 1972 played a big part in my early love for the outdoors. There on the island I experienced a life lived close to the rhythms of the birch and hemlock, the trout and loons. It was a life I knew I wanted. I was curious how these early, perhaps glorified, memories would measure up to what is there. And I worried that perhaps age and the mess of life would intrude on the simple beauty of being there.

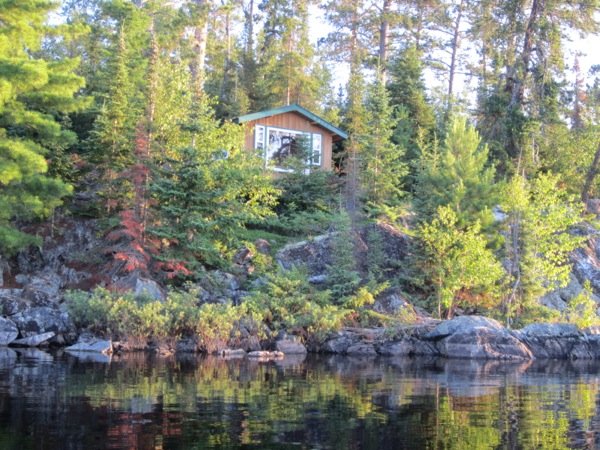

Except for a new large cabin built by my cousin Andrew, the island is remarkably the same as I remembered it. The light in the main cabin remains muted, perfect for games of backgammon or scrabble. Despite some (wonderful) improvements like a propane run refrigerator, the texture of life felt the same. There is no outside world, no internet or phone. The quiet is profound beyond all of my memories. In the late evening and through the night, the stillness was punctuated by the call of loons. Morning and evening the resident baby Merlins begged for food.

Our first full day, Polly woke me in my nest in the summer cabin, perched on a southeastern bluff, with coffee and fresh blueberry muffins. We then spent the morning swimming--naked--around the island. We pulled out on Blueberry Island and ate a few freshly ripe berries and warmed up. My hands were tingling from the cold. Our swim took hours, bobbing in the cold water, back stroke, breast stroke, a bit of a crawl. The day unfolded, endless and endlessly beautiful, except for the mosquitos. They buzzed our ears, bit our ankles and hands. These Canadian mosquitos made those I had encountered in Alaska in June seem fat, dumb and slow. These mosquitos had speed and agility on their side. I could smack one and it would rebound--flying off to bite again.

By late afternoon we were ready to venture out onto the water again, this time in a canoe. To fish. "You need to provide us with dinner, cousin," I said in mock seriousness. Polly had shopped for food for five for this week--we hardly needed any food. But I loved the idea of eating our own fish. I didn't bring up how it was going to get from the water to our plates.

We explored neighboring islands while Polly cast, and reeled in the line. The act alone felt right and good, the time meandering a pleasure.

So it surprised us both when Polly snagged the fish. It hardly struggled, but rather landed peacefully in the net I held. "Smallmouth bass," she said. It lay on the bottom of the tin canoe, without flopping or flipping. Later, we read about smallmouth bass: When hooked near the surface a smallmouth will ordinarily jump high into the air and can often shake the hook or lure from its mouth. When hooked in deep water the fish is a determined, powerful fighter, and even after it has been landed it flares its fins, clamps its jaw, and continues to look and act belligerent. The smallmouth bass is a fish that just won't quit." Really? So our fish's resigned calm became a mystery. But more: isn't fishing the most metaphorical of activities? In 1972 that fish had taught me about persistence, had given me insights into my little life, had maybe even contributed to the writer I have become. Forty years later, I wanted the same insight-inspiring sort of fight. Instead, this weak foot-long smallmouth bass had deprived me of some dazzling metaphorical insight about human nature, life and death. I was feeling mildly cheated as we made our way back to shore.

I quickly struck a deal: you kill the fish. I'll cook it. I saw that I had left Polly with the dirty work. She agreed, but she needed to be reminded of how to clean the fish. I fetched the Joy of Cooking, which contains information on killing and cleaning everything from snapping turtles to snipe and woodcock (I learn the entrails of woodcock are good flambed briefly in brandy).

Polly had no trouble scaling the fish. Then I read, as if from the Bible itself: "Next, draw the fish. Cut the entire length of the belly from the vent to the head and remove the entrails. They are all contained in a pouchlike integument which is easily freed from the flesh, so evisceration need not be a messy job." I contemplated the words integument and evisceration looking out on the water, while Polly executed her task. I read on, channeling Erma Rambauer, taking Polly through the steps of cleaning the fish. Polly's cleaning was a neat job. Erma would have been proud, and so was I.

Our fishing had not led me to thoughts on tenacity, strength, life and death. But as I stood there, looking at the lake, I saw that the real story is about cleaning the fish, facing the pouchlike integument. So much of life is about facing the pouchlike integument.

Our fish was tender and delicately flavored cooked in butter with lemon on the side. I thanked my cousin who had remembered to buy lemons, who had cleaned that fish without complaint. As we ate our simple meal, I felt that forty years had passed and yet no years had passed. We watched an orange sunset as calm settled over our isolated island.

Cousin Polly fishing; my cabin and writing retreat; sunset